Balancing Yin and Yang: The Core of Feng Shui Principles

Understanding Yin and Yang

In Chinese philosophy, Yin and Yang form the bedrock of Feng Shui practice. These dual forces, while seemingly opposite, actually complement each other in a perpetual dance of equilibrium. The dark, cool, and passive Yin contrasts with the bright, warm, and active Yang, yet both are necessary for wholeness. This duality manifests everywhere - from the changing seasons to human physiology.

When applied to living spaces, this philosophy suggests that environments should contain elements of both energies. A room with only Yang characteristics might feel harsh and overstimulating, while one dominated by Yin could become lethargic and dull. The art lies in blending them appropriately for each space's purpose.

The Interplay of Yin and Yang

Rather than fixed states, these energies constantly transform into one another. Morning sunlight (Yang) gradually yields to evening shadows (Yin). In home design, this translates to creating transitional spaces that allow energy to flow naturally between areas of different intensities.

Consider how doorways connect rooms - they serve as thresholds where energy transforms. Using rounded arches rather than sharp angles can facilitate this energy transition more smoothly, embodying the fluid relationship between the two principles.

Yin Energy in Feng Shui

Spaces meant for repose benefit from Yin's calming influence. Bedrooms particularly require this energy for restorative sleep. Research shows that cooler color temperatures (2700-3000K) in lighting actually promote melatonin production, demonstrating how ancient wisdom aligns with modern science.

Textural elements also contribute significantly - plush area rugs, velvet drapes, or upholstered furniture all enhance Yin qualities. Even the shape of furnishings matters; rounded edges and organic forms support Yin better than sharp geometric designs.

Yang Energy in Feng Shui

Active spaces like home offices or kitchens thrive with Yang energy. The strategic use of lighting creates dramatic effects - track lighting or pendant lamps over work areas boost focus and productivity. Reflective surfaces like polished stone countertops or metallic finishes amplify light, increasing the Yang effect.

Interestingly, the placement of Yang elements should consider solar patterns. East-facing rooms naturally receive morning sunlight, making them ideal for breakfast nooks or exercise areas where Yang energy supports morning activities.

Balancing Yin and Yang in Your Home

The bathroom presents an interesting case study in balance. While water elements suggest Yin, the frequent use of mirrors and often bright lighting creates Yang. The solution lies in layering - dimmable lights, plush towels, and natural stone surfaces can soften the inherent Yang of this space.

Entryways similarly require careful balancing. They should feel welcoming (Yin) yet energizing enough (Yang) to transition from outside to inside. A console table with rounded edges (Yin) beneath a striking mirror (Yang) with warm lighting achieves this perfectly.

The Significance of Balance in Feng Shui

True balance isn't about equal parts Yin and Yang everywhere, but rather appropriate distribution according to each space's function. A media room might lean Yang for entertainment value, but should incorporate enough Yin (acoustic panels, comfortable seating) to prevent sensory overload.

This principle extends to room proportions as well. Very high ceilings feel overwhelmingly Yang unless balanced with Yin elements like low furniture groupings or drapery that visually lowers the ceiling height.

Practical Applications of Yin and Yang

Art selection provides excellent opportunities for balance. A bold, colorful abstract painting (Yang) hung opposite a serene landscape (Yin) creates visual equilibrium. Similarly, mixing materials - say, a sleek metal lamp (Yang) on a rough-hewn wooden table (Yin) - achieves harmonious contrast.

demonstrates these principles in action. Notice how the bright window area balances with darker furnishings, and how angular architecture softens with curved decor elements.

demonstrates these principles in action. Notice how the bright window area balances with darker furnishings, and how angular architecture softens with curved decor elements.

Recognizing Yin and Yang in Your Home

Understanding the Yin and Yang Concept

Modern neuroscience confirms what Feng Shui practitioners have long known - our environments profoundly affect our nervous systems. Studies show that spaces with proper Yin-Yang balance actually reduce stress hormones while improving cognitive function.

This explains why some rooms instinctively feel right while others cause discomfort. The proportions, colors, lighting, and even sound qualities all contribute to this energetic balance that we perceive viscerally before analyzing intellectually.

Yin Energies in Your Home

Creating effective Yin spaces goes beyond superficial decor choices. Consider the sensory experience holistically - the whisper of fabric, the faint scent of lavender, the gentle play of shadow. These subtle elements work together to create true sanctuary spaces.

In bedrooms, the bed itself becomes the primary Yin anchor. Positioning it with a solid headboard against a wall (mountain energy) provides psychological security, while keeping electronics (Yang) at bay preserves the restful quality.

Yang Energies in Your Home

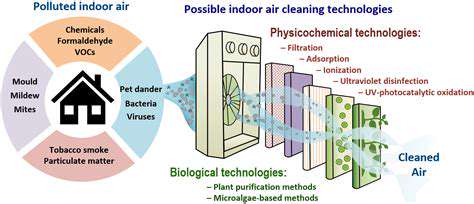

Productivity spaces benefit from Yang's stimulating qualities, but require careful calibration. Overly bright, sterile home offices can cause eye strain and mental fatigue. The solution? Layer lighting - overhead for general illumination, task lights for focused work, and perhaps a small salt lamp for subtle Yin counterbalance.

Even in Yang-dominant spaces, incorporating living elements like plants or a small water feature introduces beneficial Yin, creating what designers call productive calm - energized yet not anxious.

Identifying Imbalances

Physical symptoms often reveal energetic imbalances. Do you consistently avoid certain rooms? Feel restless in spaces meant for relaxation? These reactions indicate mismatches between a space's energy and its intended function.

Simple diagnostic methods include observing where pets prefer to rest (they naturally seek balanced energy) or noticing where houseplants thrive versus struggle. These organic indicators often reveal what our conditioned minds overlook.

Balancing Yin and Yang in Different Rooms

Children's rooms present unique challenges, needing both restful Yin for sleep and playful Yang for activity. Zoning the room effectively addresses this - perhaps a canopy over the bed creates a Yin cocoon, while an open play area with bright colors encourages Yang energy.

The kitchen, traditionally Yang, benefits from Yin touches like wooden cutting boards or ceramic canisters to soften the hard edges of appliances. Even the refrigerator's constant hum represents Yang that might need balancing with soft music or a small fountain's sound.

The Importance of Natural Light and Ventilation

Light quality changes throughout the day, and smart design works with these shifts. North-facing rooms receive cooler light (Yin), ideal for studios or libraries. South-facing spaces get intense light (Yang), perfect for sunrooms or active family areas.

Cross-ventilation creates literal energy flow, preventing stagnant air (excess Yin) while avoiding harsh drafts (excess Yang). The ancient practice of air washing spaces by opening opposite windows aligns remarkably with modern building science principles.

Feng Shui Principles for Balancing Yin and Yang

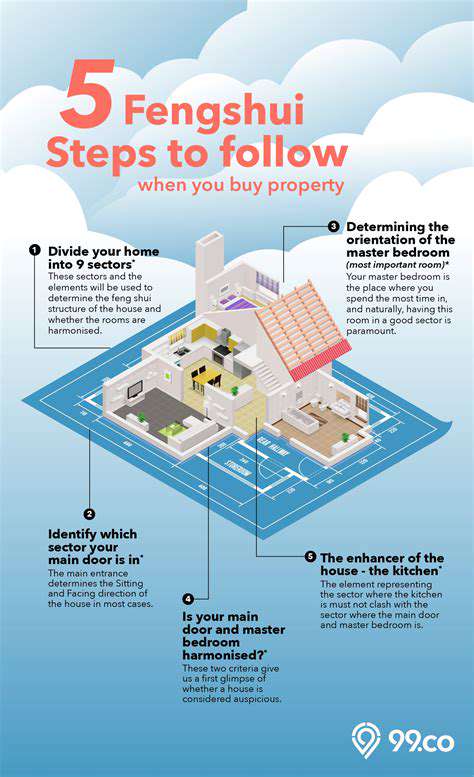

Contemporary interpretations adapt traditional principles for modern lifestyles. Open-plan homes, for instance, require special attention to create energy differentiation. Area rugs, lighting zones, and strategic furniture placement can define spaces energetically without physical walls.

Even in small apartments, creating a clear progression from Yang entry to Yin bedroom, with transitional living spaces between, establishes healthy energy flow. The key lies in intentional design rather than default arrangements.

The Interplay of Yin and Yang in Different Rooms

The Fundamental Concept of Yin and Yang

Contemporary physics echoes this ancient wisdom - from wave-particle duality to quantum entanglement, science increasingly recognizes the fundamental interconnectedness of apparent opposites. This validates Feng Shui's premise that our living spaces participate in this universal dance of energies.

The practical implication? When we align our environments with these natural principles, we experience greater harmony and less friction in daily life. The space literally works with rather than against us.

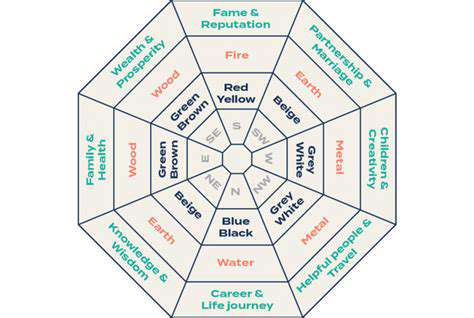

The Visual Representation and Symbolism

The Taijitu's curved line reminds us that division isn't absolute - there are always exceptions and gradations. In home design, this translates to avoiding stark dichotomies. Even in a Yang office, a Yin reading nook might nestle in a corner, and vice versa.

This symbol also suggests that energy moves in spirals rather than straight lines - a principle evident in winding garden paths or curved furniture arrangements that feel more natural than rigid grids.

Yin and Yang in Nature

Biophilic design research confirms that spaces incorporating natural patterns (fractals, organic curves) reduce stress. These forms inherently balance Yin and Yang - think of a tree's strong trunk (Yang) supporting delicate leaves (Yin), or a stream's persistent flow (Yang) within soft banks (Yin).

When we bring these natural balances indoors through materials, shapes, and living elements, we tap into deep evolutionary preferences that promote wellbeing.

Yin and Yang in Human Health

Chronobiology research shows how our circadian rhythms depend on daily cycles of light (Yang) and dark (Yin). Modern homes often disrupt this with constant artificial light. Smart lighting systems that mimic natural daylight cycles represent a technological solution to this ancient wisdom.

Similarly, the recent emphasis on sleep hygiene mirrors Feng Shui's bedroom recommendations - cool, dark, quiet spaces that honor our biological need for Yin restoration.

The Dynamic Nature of Change

Seasonal decor rotations align with this principle - lighter fabrics in summer (Yang), heavier in winter (Yin). But deeper applications involve designing flexible spaces that can adapt to changing needs over years, avoiding the stagnation that comes with overly fixed arrangements.

Yin and Yang in Society

As remote work blurs home-office boundaries, these principles gain new relevance. Creating clear energetic distinctions between work (Yang) and personal (Yin) spaces within the same physical area prevents burnout. This might involve visual cues (changing lighting scenes) or ritual actions (closing a laptop cover) to mark transitions.

The pandemic taught us that homes must serve multiple functions - these ancient principles provide a framework for doing so harmoniously. By consciously shaping our environments, we shape our experiences within them, for greater wellbeing in challenging times.